Evals are all you need

Last month, I built an app called Taralli. It was fun to close the loop and get it out there. Still - there was an elephant in the room:

"...[calorie tracking] Accuracy isn’t great, and it makes some pretty basic mistakes. I’ve got plans to fix that..."

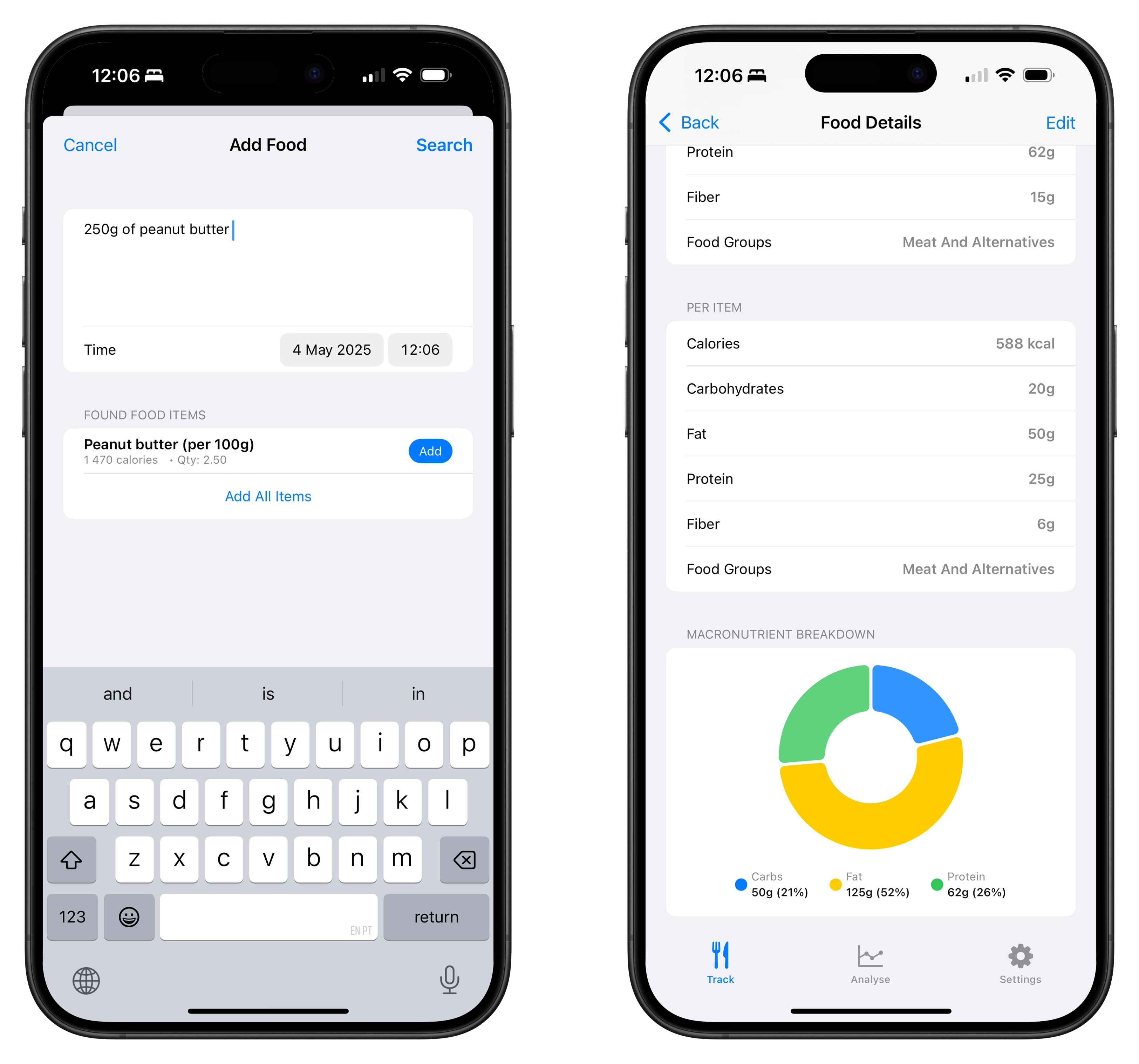

And things started failing pretty early. 100g of peanut butter came back with 58 000 kcal - 350g of pasta as 60 000 kcal - quantities were all over the place. And even though most users were giving me good feedback - It was time to fix things. After some work, I managed to improve tracking accuracy from 17% to 76%. It turns out, evals are all you need.

Naive is good, but it fails eventually

I constantly preach about how we shouldn't build complicated things before knowing if they're actually going to be used. Taralli's first system for calorie counting was embarrassingly simple. All it did was take a user's food description as a string - pass it through gpt-4o-mini with structured outputs, and generate a JSON response. Here's the Pydantic model that gives that JSON format:

class FoodGroup(str, Enum):

dairy = "dairy"

meat_and_alternatives = "meat and alternatives"

grain = "grain"

fruit = "fruit"

vegetable = "vegetable"

class FoodItem(BaseModel):

name: str = Field(description="The name of the food item")

quantity: float = Field(

description="The quantity of the food item in the user's description"

)

calories: float = Field(

description="Calories in kilocalories (kcal) for a single unit of the food item"

)

carbs: float = Field(

description="Carbohydrates in grams for a single unit of the food item"

)

fat: float = Field(description="Fat in grams for a single unit of the food item")

protein: float = Field(

description="Protein in grams for a single unit of the food item"

)

fiber: float = Field(

description="Fiber in grams for a single unit of the food item"

)

food_groups: list[FoodGroup] = Field(

default_factory=list,

description="The food groups to which the food item belongs",

)

class NutritionAnalysis(BaseModel):

food_items: list[FoodItem] = Field(

description="A list of food items with their nutritional information"

)

With this in place - it's relatively simple to build an API that does the following:

Input: a handful of peanuts, output:

{

"food_items":[

{

"name":"peanuts",

"quantity":0.5,

"calories":414.0,

"carbs":16.0,

"fat":36.0,

"protein":19.0,

"fiber":8.0,

"food_groups":[

"meat and alternatives"

]

}

]

}

The system returns not only calories but also macronutrients (carbs, fat, protein, fiber, and food groups). And even though the model respected the format almost 100% of the time, cracks started showing pretty quickly:

Input: 100g of peanut butter, output:

{

"food_items": [

{

"name": "peanut butter",

"quantity": 100.0,

"calories": 588.0,

"carbs": 20.0,

"fat": 50.0,

"protein": 25.0,

"fiber": 6.0,

"food_groups": [

"meat and alternatives"

]

}

]

}

Wait a second, 100 x 588? That’s 58,800 calories for 100g of peanut butter. That’s wildly off (the model is misinterpreting what I want for quantity here). It should have set name to "100g of peanut butter" and quantity to 1. For example.

Creating a golden dataset

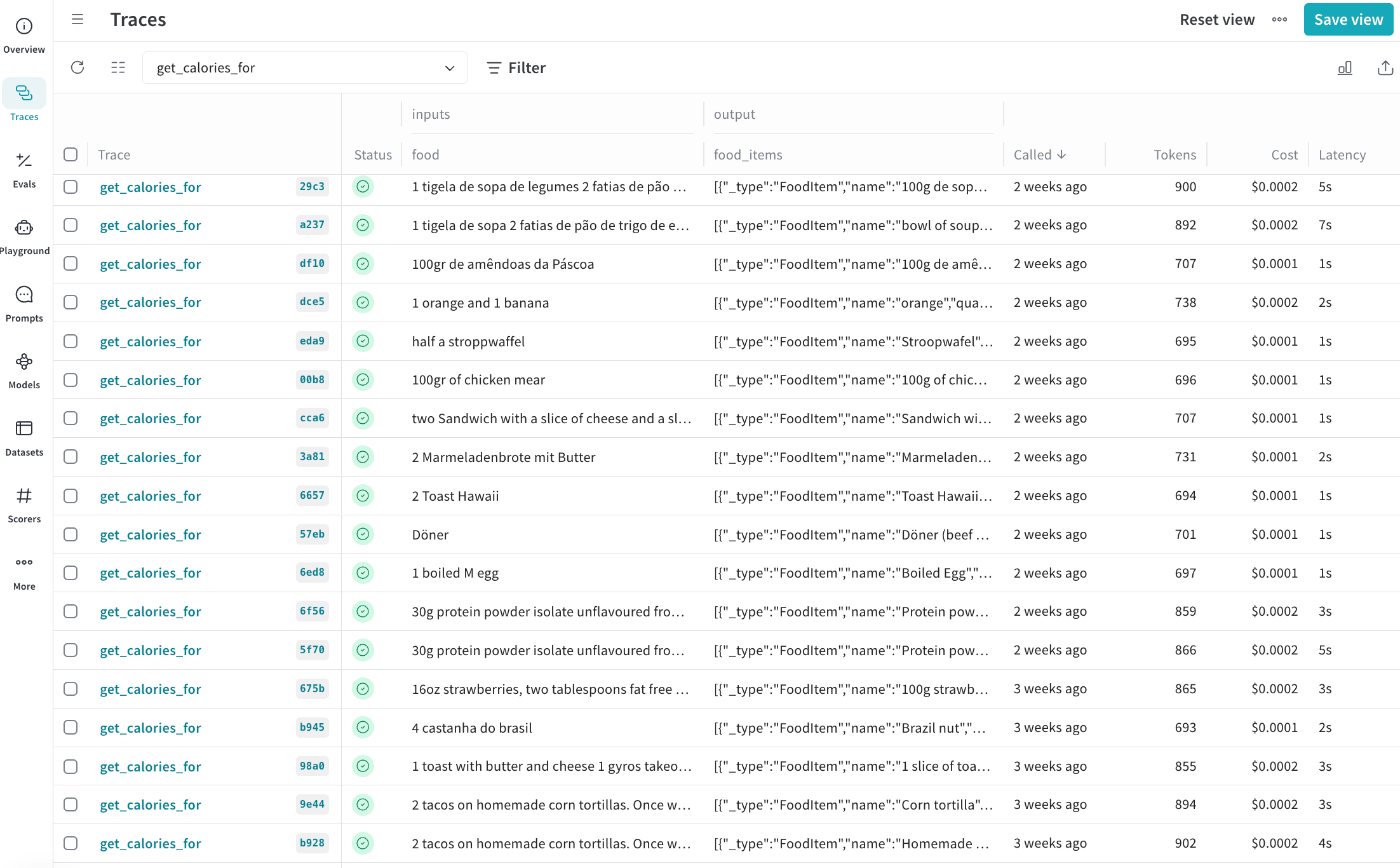

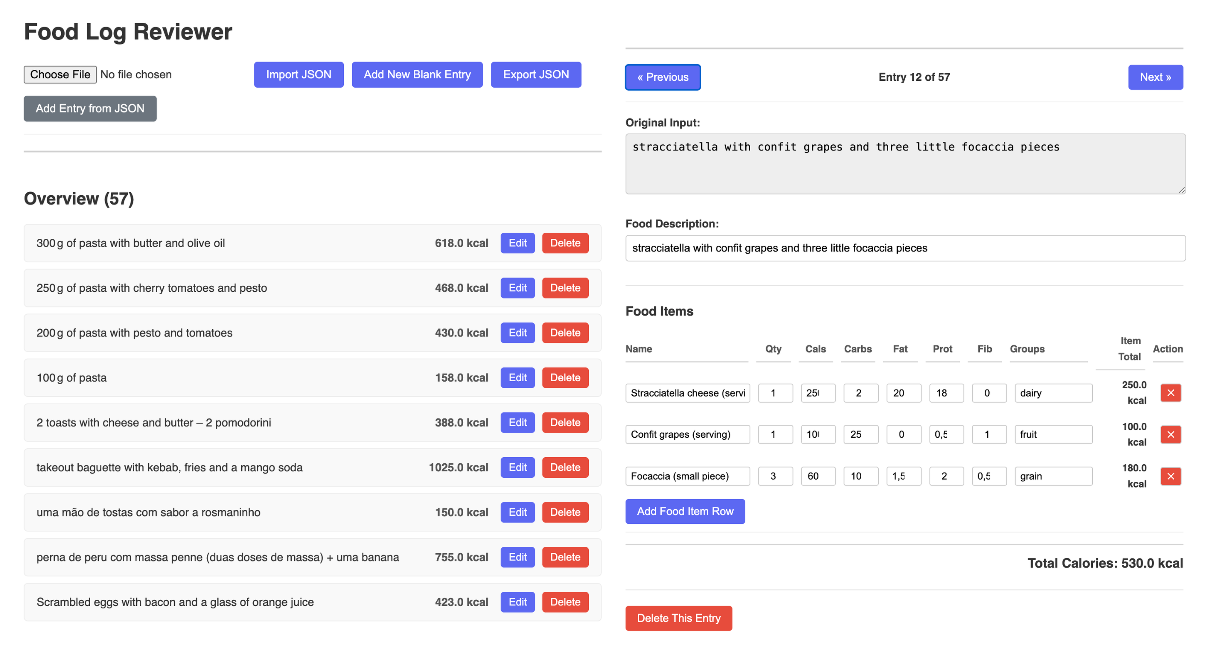

When I published Taralli, I made the app completely free (even though I was paying for every LLM call). I did warn users that I was logging all of their inputs into the food tracking model. Using W&B Weave and a simple decorator, I was able to log every input-output of the system.

That allowed me to start capturing real-world examples of where the prompt was failing. Looking through the data, I found several cases where my zero-shot prompt was just not cutting it (wrong food groups, lots of wrong quantities). Using this data, I started collecting a golden dataset: a collection of food descriptions and their corresponding nutritional analysis. Using OpenAI's o3 and Google's Gemini 2.5 Pro - I was able to make sure all the quantities, descriptions, and food groups were exactly like I wanted them.

But I still wanted a way to visualize, edit and update the dataset. So I built a small visualizer where I could see everything that was going on, and edit whatever was wrong. 200% vibe coded.

A simple metric

With my golden dataset in place, I needed a way of evaluating whether a given prediction from the prompt was good or bad. By looking at my entries - the most common mistakes were pretty obvious. Either it was calorie totals - or missing food groups.

My approach was very basic (again) - and could be even more refined. Given a certain food description:

- Is the total calories of the prediction within 10% of the total calories of the golden example?

- Is there an overlap between the food groups of the golden example vs. the predicted one?

If the answer to both questions is 'Yes' - then the prediction is good. In code, that roughly translates to:

def eval_metric(example, pred, trace=None) -> bool | float:

gold_items = [dict(i) for i in example.food_items]

pred_items = [dict(i) for i in pred.food_items]

def _totals(items: list[dict[str, Any]]) -> tuple[float, set[str]]:

calories = sum(i["calories"] * i["quantity"] for i in items)

groups: set[str] = set().union(*(i["food_groups"] for i in items))

return calories, groups

gold_cal, gold_groups = _totals(gold_items)

pred_cal, pred_groups = _totals(pred_items)

calories_ok = math.isclose(gold_cal, pred_cal, rel_tol=0.10)

if gold_groups or pred_groups: # at least one side has groups

groups_ok = bool(gold_groups & pred_groups)

else:

groups_ok = True # both lists empty

sum_ok = calories_ok + groups_ok

is_ok = sum_ok == 2 # if both are ok

return is_ok

Now that we have a metric - we can make number go up.

Using DSPy to Improve the Model

The first step was to use DSPy, a framework I've talked about before, to evaluate our current performance. After splitting my golden dataset into training and testing splits, and I had my metric ready, I could easily assess how well my current system was performing:

def process_example(val_example):

pred = classify_food(val_example.food_description)

return eval_metric(val_example, pred)

with concurrent.futures.ThreadPoolExecutor() as executor:

results = list(executor.map(process_example, val_set))

Which resulted in:

=====EVALUATION=====

example.food_description='a banana'

gold_cal=105

pred_cal=105

CALORIES_OK? True

gold_groups={'fruit'}

pred_groups={<FoodGroup.fruit: 'fruit'>}

GROUPS_OK? True

is_ok=True

=====EVALUATION=====

example.food_description='300 g stew with chicken, potatoes and vegetables'

gold_cal=270

pred_cal=360

CALORIES_OK? False

gold_groups={'vegetable', 'meat and alternatives'}

pred_groups={<FoodGroup.grain: 'grain'>, <FoodGroup.vegetable: 'vegetable'>, <FoodGroup.meat_and_alternatives: 'meat and alternatives'>}

GROUPS_OK? True

is_ok=False

# more examples, truncated for brevity..

Score: 17.24%

The score of my production system on the dataset was only about 17%, not great - we know. To get yet another baseline for my system, I first tried using Gemini 2.5 Flash, as I wanted to keep costs reasonable while still getting better performance. I evaluated it on the dataset using DSPy:

classify = dspy.Predict(NutritionAnalysis)

gemini_flash_preview = dspy.LM("openrouter/google/gemini-2.5-flash-preview:nitro")

with dspy.context(lm=gemini_flash_preview):

evaluator = Evaluate(

devset=val_set,

num_threads=10,

display_progress=True,

display_table=len(trainset),

)

evaluator(classify, metric=eval_metric)

# Average Metric: 7.00 / 28 (25.0%): 100%|██████████| 29/29 [00:00<00:00, 960.39it/s]

# 2025/04/30 19:46:41 INFO dspy.evaluate.evaluate: Average Metric: 7.0 / 29 (24.1%)

Using this zero-shot approach, the score was about 25% - better than my GPT-4o mini implementation, but still far from acceptable for users.

I decided to try another DSPy optimization technique called BootstrapFewShotWithRandomSearch. This approach finds optimal examples from the training dataset to include in the prompt, which can dramatically improve performance. Here's the code:

with dspy.context(lm=gemini_flash_preview):

tp = dspy.BootstrapFewShotWithRandomSearch(

metric=eval_metric, max_labeled_demos=16, num_candidate_programs=16

)

bootstrap_fewshot_random_search = tp.compile(

classify.deepcopy(),

trainset=trainset,

valset=val_set,

)

# final evaluation

with dspy.context(lm=gemini_flash_preview):

evaluator = Evaluate(

devset=val_set,

num_threads=10,

display_progress=True,

display_table=len(trainset),

)

evaluator(bootstrap_fewshot_random_search, metric=eval_metric)

# Average Metric: 22.00 / 29 (75.9%): 100%|██████████| 29/29 [00:00<00:00, 3096.37it/s]

# 2025/04/30 19:46:45 INFO dspy.evaluate.evaluate: Average Metric: 22 / 29 (75.9%)

After a few minutes of optimization and testing, we achieved 76% accuracy on our validation dataset - an incredible improvement over both our previous system and the zero-shot approach.

There is a trade-off: the optimized prompt includes several few-shot examples, which can impact response time. However, since we're using the relatively fast Gemini 2.5 Flash model, it doesn't matter that much.

We can see that for our problematic example of "100 g of peanut butter," the new model now provides a much more reasonable result:

with dspy.context(lm=gemini_flash_preview):

print(bootstrap_fewshot_random_search(food_description="100 g of peanut butter"))

# Prediction(food_items=[FoodItem(name='Peanut butter (100g)', quantity=1.0, calories=588.0, carbs=20.0, fat=50.0, protein=25.0, fiber=6.0, food_groups=['meat and alternatives'])])

Here's the full prompt that DSPy uses for the example above. As you can see, it's essentially a few-shot approach to solving the problem, and it works surprisingly well.

Integrating the Improved Model

Now that we have an optimized prompt that performs well, we can save it and integrate it into our FastAPI application:

# save our dspy program

PATH_TO_PROMPT = "../optimized_prompts/bootstrap_fewshot_random_search.json"

bootstrap_fewshot_random_search.save(PATH_TO_PROMPT)

# create a function to process food descriptions

def get_classifier_async() -> dspy.Predict:

lm = dspy.LM(LM_NAME)

dspy.settings.configure(lm=lm, async_max_workers=4)

dspy_program = dspy.Predict(NutritionAnalysis)

dspy_program.load(PATH_TO_PROMPT)

dspy_program = dspy.asyncify(dspy_program)

return dspy_program

# create an async processor

DSPY_PROGRAM = get_classifier_async()

@weave.op()

async def get_calories_for_dspy(food: str) -> NutritionAnalysis:

logger.info(f"Getting calories for {food}")

result = await DSPY_PROGRAM(food_description=food)

food_items = result.food_items

food_items = [_.model_dump() for _ in food_items]

parsed_message = NutritionAnalysis(food_items=food_items)

logger.info(f"Got response: {parsed_message}")

if not isinstance(parsed_message, NutritionAnalysis):

raise ValueError("Expected NutritionAnalysis response")

return parsed_message

# integrate it into our fastapi application

@app.post(

"/calories-v2",

response_model=NutritionAnalysis,

description="Get calories for a food item from request body using DSPy.",

)

async def get_calories_v2(request: FoodRequest, api_key: Optional[str] = Header(None)):

"""Get calories for a food item from request body using DSPy."""

if api_key != API_KEY:

raise HTTPException(status_code=403, detail="Invalid or missing API Key")

return await get_calories_for_dspy(request.food_description)

Along with some other new features in Taralli, I integrated this new API endpoint, and now all users of the app benefit from our improved food prediction model, which is much more accurate and an overall better experience. Still room for improvement though!

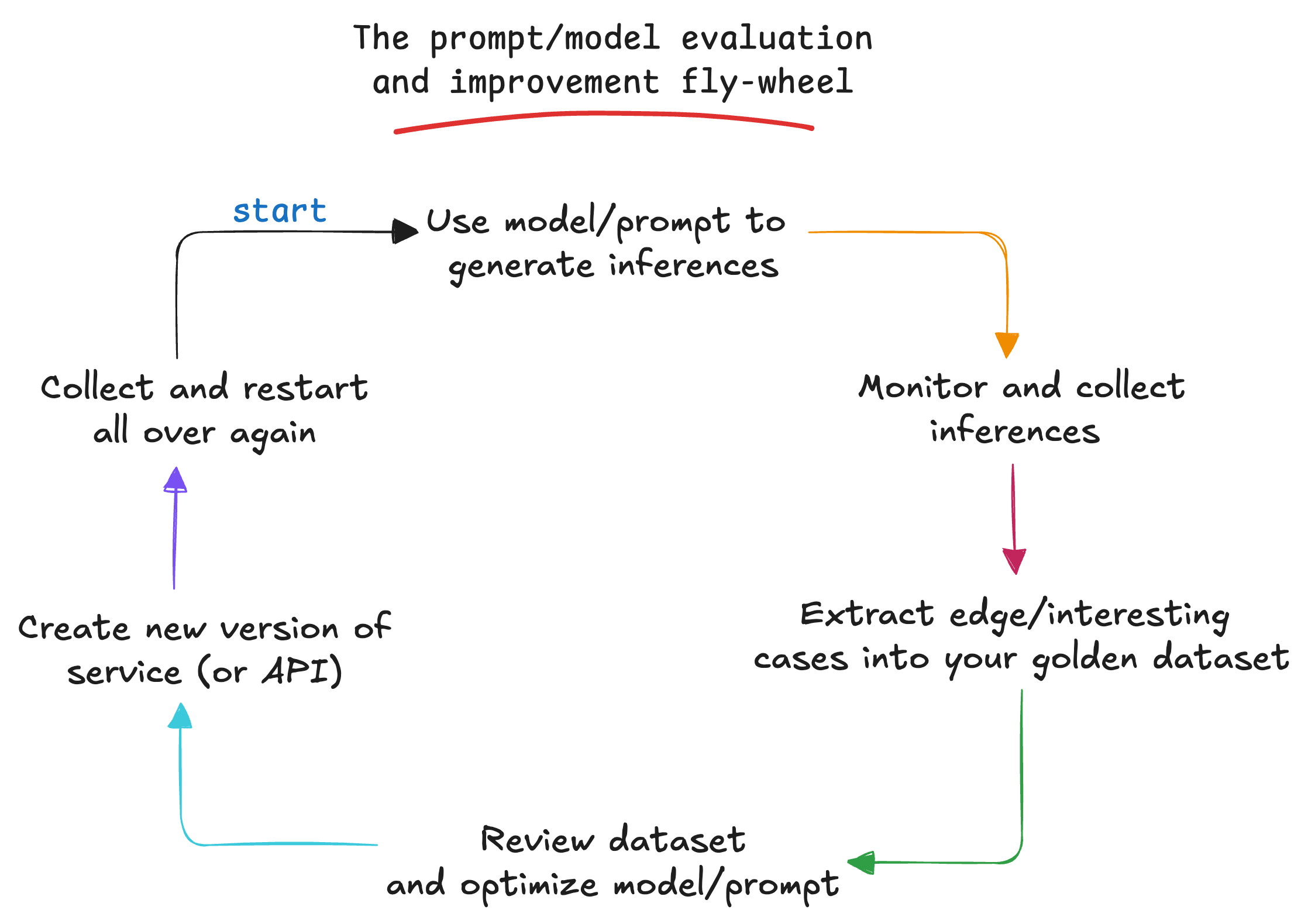

The Flywheel Effect

What I like about this approach is that it creates a flywheel effect. As more users interact with the app, I collect more data, I can correct/review that data and add it to my golden dataset. This flywheel allows me to continuously update the prompt as we go.

Final thoughts

I've seen many projects in the wild just using a prompt or model and leaving it as is. Without a good idea of how good (or probably bad) it really is. My first step - is - as always - just put it out there. There are just too many unknowns to get stuck on the 0 to 1 stage.

Once things are out there, then it's time to start asking yourself: OK - what does good look like? With some simple monitoring, you'll start understanding what REALLY matters. Once that's done - then - evaluations are truly all you need.

Also - check out Taralli - and let me know what you think!